Since the early part of the 20th century our identities have been partial and incomplete. I imagine the last unitary human beings populated Victorian manses. Their mail was delivered several times a day, they had more culture than one could shake a stick at and several servants to take the edge off an otherwise brutal, short and ugly sojourn through the world.

As performance art approaches the event horizon of real life it must make evident its own incompleteness. This isn’t a new idea. Robert Filiou mapped out the terrain and Yoko Ono made it into a maxim 40 years ago. But watching Robin Brass’s performance last night at CRAB Beach (Create A Real Beach) I was taken by the intentional incompleteness of her performance.

Many pieces at the festival contain significant elements that are hidden or obscured from the audience. Li Yilin’s piece in the alley next to Hastings Street is an example. He placed small pieces of paper into the cracks of telephone poles. He climbed a ladder to find the cracks high on the poles. We in the audience could not see the paper nor were we informed what, if anything might be imprinted on those tiny bits of yellow paper.

Again in Him Lo’s piece on Saturday night we weren’t told why he had painted his body in black acrylic paint or why he was wearing a white shirt and tie while holding a mop.

In the first example, the images on the bits of paper were supposedly pictures of Canada’s most wanted criminals. In the second, Him Lo painted himself black to symbolize depressive episodes and he wore the white suit and tie because his late father wore these. His father also worked as a janitor.

I learned these facts by talking with people at the events and to the artists after the performances. Members of the audience who did not have the opportunity to speak to the artists or someone-who-was-in-the-know were just shit-out-of-luck.

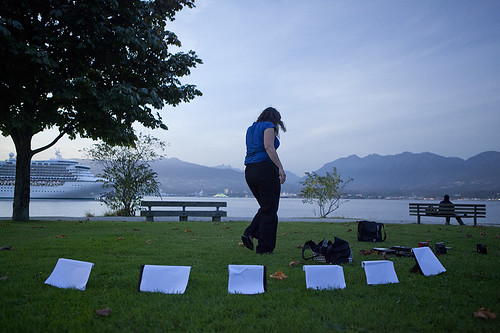

Robin Brass began her performance minutes before sunset by setting out on the grass four playback devices and seven picture frames each covered with a blank sheet of paper. From a sack, she spilled out onto the grass behind the line of frames a pile of old audio-cassette tapes and real-to real videotapes. These she proceeded to un-spool, gathering together a tangled mass of shiny Mylar.

The playback devices, two cassette players, a CD player and a mini-cassette player provided a soundtrack of voices of old men and what I thought to be the sound of horse’s hooves on hard ground. The words spoken were unclear.

She unveiled the seven photos, which were old photos of groups of encampments of teepees and of Native Americans in ceremonial dress; other photos seemed to be of family groups, others were of army or policemen.

Undistracted by the landing and taking off of the Helijet at the heliport just behind her, Brass brought the piece to a conclusion by turning one of the photo frames away from the audience so that it faced toward the pile of tangled Mylar and a thick stack of paper. She sat on the paper and threw herself backwards onto the mass of tangled tape. One by one with all the photos she repeated this action and the piece ended. It was dedicated to her sons.

It was only in talking to Brass after the performance that I learned a number of interesting facts. (I had been drinking a bit before this conversation so please forgive any errors, omissions, elisions, confusions, conflations, miscomprehensions, exaggerations, misrepresentations or general stupidities.) Her father was an archivist and historian who died suddenly some years ago. The stack of paper that sat on the grass was a copy of his historical research of four Native American communities in the Qu’appelle valley. The audio playback was of his interviews with elders and song keepers of those communities.

The four communities were forcibly and deceitfully brought together in the late nineteenth century to become one of Canada’s “model” reservations. These models were subsequently used to inform the creation of the South African apartheid system.

Further the photos showed us people of those communities some of whom were related to Brass. The great aunts and uncles and cousins of Brass’s sons to whom the piece was dedicated.

These facts, which provide a rich context to the work, remain unknown to those who witnessed the live performance. It’s only through a direct engagement with the artist that the work’s meaning unfolds. A bit like real life.

FA

Showing posts with label Robin Brass. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Robin Brass. Show all posts

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Robin Brass at Crab Park

A crowd of us gather in a secluded part of Crab Park next to a weathered looking torii and a ginkgo tree. In the dying light of the day, we have come to witness Robin Brass perform. Out of a shopping bag, she takes out some simple sound equipment: some mini amps, shoebox recorders, a discman, and a handheld tape recorder. The voice of a man floats through the air, his voice older, distorted, hard to hear in this open space. Other materials reveal themselves. Seven picture frames, covered with pieces of white paper, are placed in a semi-circle facing the audience. There is a big stack of papers, bound together. A bag is dumped out with reels and reels of cassettes and magnetic tape.

A voice loops, the syllable "Wo-wo wo" adding a meditative rhythm to the piece. Holding on to the end of the tape, Brass tosses the plastic canisters to the wind, pulling in lengths of tape in large, swooping movements. These beautiful gestures cause masses of tape to gather in a cloud around her arms and flutter in the breeze. Tape is yanked out of its cassette casing. It all gathers in a big pile at the centre of the space Brass has created. She tosses the canisters as far as they will go, reeling them in.

The audience moves in closer to peer at what is in the picture frames, as Brass uncovers them. All are photographs in black and white. One shows a figure walking along a railroad with a dog. Another shows a group of painted tipi tents. Mostly we see group portraits of First Nations people from a time gone by. Where they were found is not disclosed.

As more tape is unraveled, a helicopter passes loud and low over our heads. Brass' movements grow more frantic, more exhausted. Orange light shines through the mist over the ocean. Finally I am able to pick up some of the audio, snippets of "Sit down, fall asleep" and perhaps "all the songs in the songbook." Brass plugs in an amp and we hear a rhythmic clacking sound like a train.

All sounds disappear except the syllables "Wo-wo" which, come to think of it, also sound a bit like a train. As a final action, Brass holds each picture towards the audience, then towards the sea and the fading sun. After placing each picture back in its place, but facing inward and away from us, she sits on the big stack of paper and lets herself fall into the mass of tape, once for each photograph. As the sound stops, we realize that it is getting dark and lights have come on in the city. It's chilly.

I am left with the impression of an archive that is revealed and destroyed. Old forms, magnetic tape, black and white photographs, paper files, are unraveled, turned away, or used as a means of collapse. Likewise the Indigenous cultural history held in these media are hidden, fragmented, elusive. Brass has given to us a poetic revival and farewell to old forms and old traditions.

- stacey ho

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)